Teachers have to hold an enormous amount of information in their head at any one time. I struggle with remembering it all (classlists, names, lesson plans, key dates… the list goes on) and it’s only within the last few years I feel I’ve got to a point where I can separate my work life and home life in a manageable way. I hate using paper to organise myself, as I have never learnt how to keep it filed sensibly. I used to have vast to-do lists scribbled down which inevitably would get lost, or be indecipherable weeks later when I suddenly realised I was about to miss a deadline. I would worry that I had not written down the due date of an assessment, or realise that there was a Parents Evening coming up but had left the details of the dates in my office. It wasn’t healthy and it meant I found it difficult to switch off from school once I got home as I was unable to compartmentalise all those things I had to remember.

I started using the calendar on my email software after seeing a colleague do it, and it blew my mind – looking back, I’m amazed I managed to function without it. I used to use my planner for everything but as the years have gone by, I no longer order one as everything I do is through my calendar. These are the most common ways I use it to help me manage my workload and maintain a healthier work-life balance:

I put all my assessment deadlines in

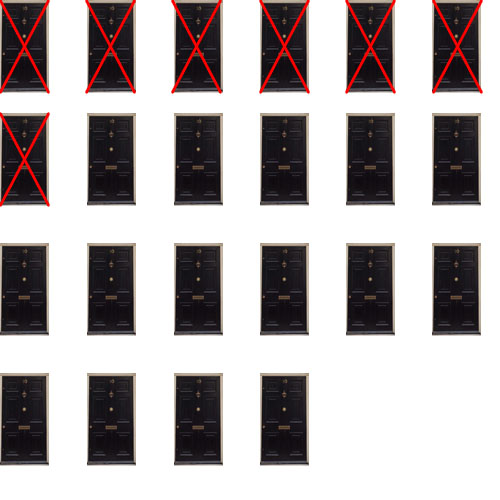

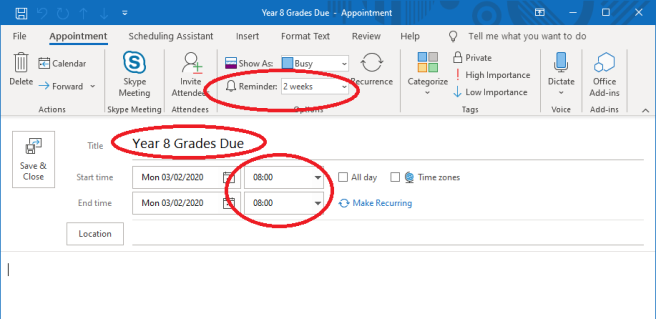

This is something I do at the beginning of the school year (it’s easy and makes me feel super-productive). It was the first thing I used the calendar for and it means I never have a deadline catch me unawares. It’s pretty easy to do and doesn’t take long – I get a list of all the assessment deadlines (exams, data drops, etc.) and then go into the calendar on Outlook. I set it up so I can see each day in the week, then scroll through each week in turn and if there is an assessment deadline on a day in that week, I double click the 8:00am slot and add a title. I leave everything else blank but make sure I choose something under ‘Reminder’ – usually 2 weeks as that gives me plenty of time in case I need to do some assessment before entering the data. This means that 2 weeks before the deadline, when I open Outlook, a little reminder will pop up to tell me about it. This notification is easily snoozed until a time nearer the deadline when I am ready to deal with it.

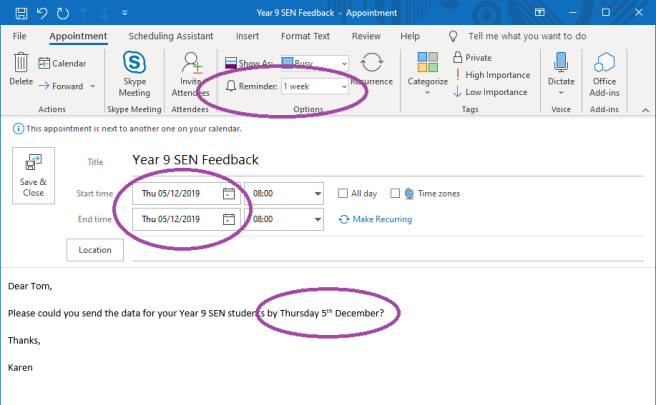

I enter important dates/times as I receive them

Occasionally I get emails asking me to do something by a certain date such as contacting a parent, or if I can complete some feedback on a student. Often I can’t deal with this at the time of reading, so I click on the email and drag it down to my calendar icon. This automatically opens an Appointment window which can be quickly edited. I change the date to when it is due, alter the reminder (usually a few days before) and save it. This gives me peace of mind that I don’t have to remember it until it is crucial and nearer the time, which helps me focus on the immediate rather than feeling overwhelmed with a mountainous to-do list.

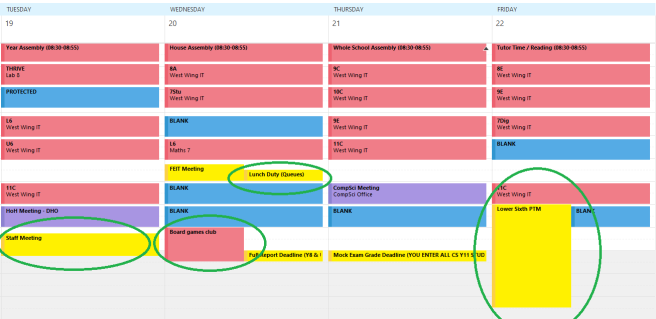

I add events that take place outside school hours

This is useful for a quick reference and I find it much easier than checking on a printout that I might mislay. It’s handy because I can always have it to hand, regardless of where I am. The process is simple: I do the same as above except put in events like staff meetings, open evenings/days, parents evenings and school holidays (!). I find it useful to put in specific times so I don’t have to check later for the start and finish of the event. I usually don’t bother adding reminders as I’m often aware of the dates coming up when I’m nearer to them.

I link my calendar to my phone

I find this really useful if I need to quickly recall the lessons I have the next day, or if I need to check whether I’m busy after school. I can also add events to my calendar if I suddenly remember I have to do something when I’m at home, and once it’s on my calendar I can forget about it until I’m back in school. I have two calendars on top of each other on my phone – my personal and my work one. Each can be turned on or off but I find this useful for things like parents evenings or other activities that take place outside the school day. This isn’t for everyone, as it does mean linking your school email account with your phone.

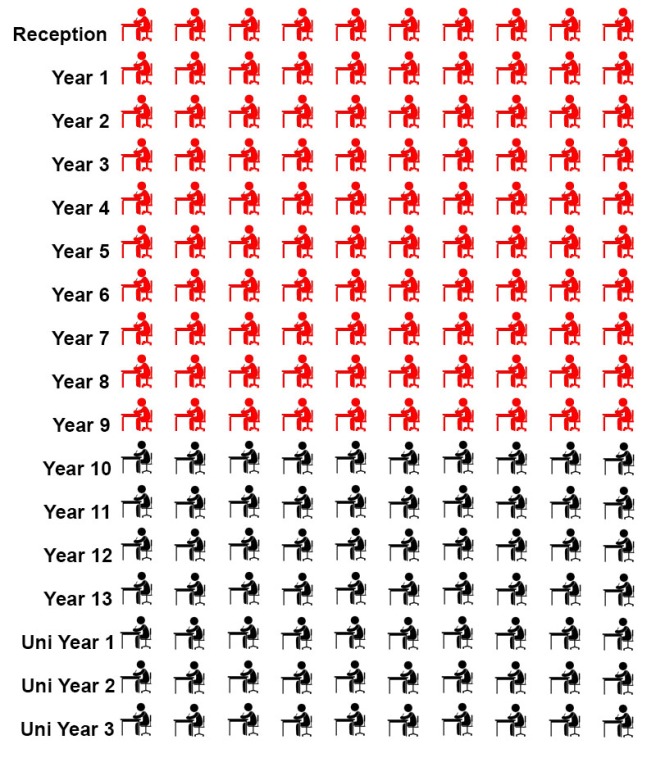

I use it to plan my lessons

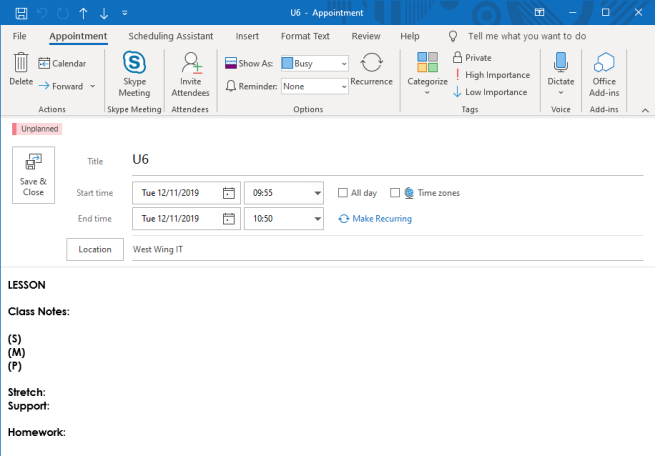

This was the biggest change in the organisation of how I teach. It takes some time as I have to set up each lesson with an ‘Appointment’ and the start and end time. I turn off reminders, and put in the following:

Not all of this has to be filled in, obviously, but I find if I have it in one then I can just copy-and-paste across to others. A whole day’s schedule can be copied by holding down Ctrl on the keyboard and selecting each lesson individually. This can then be pasted to a new day. Unfortunately the “repeat weekly” or “repeat fortnightly” doesn’t work as I’d like it to, as half-term breaks and holidays break the cycle. I copy my entire timetable across manually for these which takes some time, but no more than writing the details for each class into a planner.

I’ve found that the ability to chuck stuff into a delayed to-do list really helps me with my work-life balance as I can deal with things as needed, rather than see them mount up. I don’t worry about missing deadlines and, even though I often get 5-10 notifications pop up on Outlook each morning, it’s a relief to know my calendar has my back and stops me forgetting anything.